Moving away from a legacy system using Scala and Kafka - Part 1

The challenges of migrating our media assets management system

My team at Canal+ is building a new media asset management (MAM) platform. To put it simply, Mediahub, our platform, stores video files and information regarding these files:

- Technical information (how many audio channels does this video have? what’s the video’s resolution?)

- Editorial information (is it a movie? A show? A TV series episode? Who is speaking in the sequence? What about?)

- Legal information (when can we air this content? When did we acquire this contract?)

On top of storing and exposing tools to manipulate video files and their related metadata, Mediahub allows third parties to send us new content that can be shipped to VOD platforms and TV channels. A built-in workflow orchestration engine takes care of receiving, quality-checking, assembling and shipping footage. The platform can execute hundreds of these workflows concurrently and treats more than 3000 workflows a day.

The Mediahub project is born roughly in 2017, but a vast proportion of the video footage we manage comes from a legacy system. Out of roughly 1M medias we are managing, 900K come from the old system; a system we are trying to slowly replace, using Kafka, Scala, and functional programming as our main tools.

In this series of articles, I’ll explain why we are moving away from that legacy system and how we are doing it. I’ll go from a big picture of our architecture (ETL pipelines built on Kafka) to some neat implementation details (using Cats to sanitize loosely structured data), in an attempt to showcase how Kafka, Scala and functional programming allow us to modernize our video management tools.

- The introduction, this article, will provide some background regarding our product and our transition to a better system; it will also introduce the building blocks of our transition: Kafka topics and functional microservices written in Scala.

- The second part will cover our data migration pipelines in more detail.

- The third part will cover our functional services and showcase how Scala’s type system and neat programming concepts like algebraic data types and functors (they’re not as scary as they sound!) help us manipulate data safely and easily.

Let’s do this!

Why we are moving away

The media management platform (MAM) is at the cornerstone of our video supply chain: it is used by a thousand users daily to provide content to a hundred distribution channels across the globe. Since 2011, in virtue a contract between Canal+ and a software vendor, the role of MAM is performed by Edgar, a closed-source, monolithic program built on a long-obsolete foundation.

Our main concern with Edgar today is the impossibility of reshaping it to address new needs:

- It’s 2021. People want 4K and HDR videos. Edgar doesn’t handle them.

- We want to configure and restrict content distribution on a per-territory basis, as we expand our operations worldwide. Edgar wasn' built to do that, as Canal+ was mostly operating in France when it was introduced

- We want a multilingual application to support our expansion to new countries.

- We want to introduce new features, new distribution channels, new video transcoding workflows, quickly and without breaking what we already have.

At best, adding these changes to Edgar would require another expensive contract with a third-party vendor, assuming it possible wihout rewriting the whole thing. Rather than throwing money to maintain a 15-year-old piece of software, we’ve decided implement ourselves our MAM for the decade to come.

- We’re building in-house to avoid locking ourselves in a 15-year contract with another vendor. We’re going inner source, applying to our organisation the best practices of open-source software development: public Git repositories, shared libraries, pull requests, open issue tracker, open Wiki.

- We’re breaking free from the monolith and going full microservices. This approach lets us introduce new features as they are needed and remove them when they are no longer needed (more on that in a moment).

Replacing Edgar: the main challenges

Replacing such critical software requires time, effort, and a thoughtful approach. Here are some of the things we need to consider:

- Many of our procedures take hours to complete and involve many services. Should a dozen-hour-long process crash in the middle, it would be very wasteful to restart from the very beginning

- Long-running processes should behave correctly with limited resources and bottlenecks. We must regulate long-running processes so that the fastest stages (e.g. CRUD operations) are not overflowing the slowest stages (e.g. video transcoding) with more work than they can handle.

- Users are still using the legacy system on a daily basis. We cannot shut Edgar down until we can provide them with a replacement that is at least as good as

Edgar on every aspect. Feature-parity with the old system is not enough: we

also need to transfer decades worth of data to the new system.

- We need one-shot data replication to transfer the entirety of the data to a newly provisioned database…

- and real-time data replication so changes users make in Edgar are reflected in Mediahub immediately

- We don’t want to make a mere copy of Edgar on a more recent foundation, we want to build a radically better system, with new features. As we reimagine our video supply chain and change the underlying data model, data from the legacy will need to be translated to the new model. Fortunately, Scala’s powerful type system allows us to express these transformations safely and easily reject invalid data.

The building blocks of our architecture: Scala microservices and Kafka topics

While Edgar was a Java monolith, we’ve taken the opposite approach and built Mediahub as a distributed system, made up of 120+ microservices, the vast majority of which implemented in Scala.

While distributed systems are notoriously harder to implement and maintain (notably regarding data consistency) this approach as allowed us to handle some of the hardest challenges of migrating a critical system.

In particular, this architecture allows to segregate transitional services, which only exist to serve our transition from one platform to the other, from broader and more durable services. Indeed, Mediahub is a connected system: connected to the legacy software, whose data needs to be replicated in real time as long as it is running; and connected to external systems (third-party APIs, subsidiaries of the Canal+ group etc.). Interacting with these services requires specific code and the microservices architecture lets us separate that code from the rest of the system. Of course, even a monolith should clearly separate concerns, this isn’t something you can’t achieve without microservices; but there’s one question that a modular architecture answers very well: “What if I don’t need that anymore?”

We’ve found that being able to decommission parts of the application is just as important as adding parts to address new needs. Delivering to our users a smooth transition from the old system to the new one is crucial to our business; and the best way to achieve it is to have loosely coupled services that we can take out of from the system at any time, with little or no interruption of service.

Inter-service communication

Dividing the application into microservices forces us to be more conscientious about separation of concerns. We strive to keep a service’s boundaries small and its knowledge of the outside world limited. We ensure that services don’t know about one another, and thus don’t call one another directly, unless necessary.

A transitional service may depend on a permanent, broader service, but never the other way around, as our ability to decommission legacy-specific services lies in the fact that no other service depends on them.

While especially crucial for this whole legacy transition, limiting the knowledge components have of one another is beneficial to all parts of the platform. Regularly, some service will apply business rules in reaction to an event in another service. In this scenario, the service that emitted the event produces a message in a Kafka topic. The message will be consumed by other services without the original producer’s knowledge. Services can emit and consume events to form chains of reaction we call choreographies, we’ll discuss them later.

Kafka topics are essentially partitioned and ordered collection of events that have multiple producers and multiple consumers within a system. They are not only useful for propagating events across loosely coupled services; they enable us to build large ETL (extract, transform, load) pipelines, to move massive amounts of data from the old system to its successor. Kafka is a distributed streaming platform.

Streams let us reason about data emitted over time: they give us a declarative and composable way of handling massive — possibly infinite — amounts of data, which are modelled as successive and bounded sequences of elements.

In a video about a year ago, I’ve shown how fs2, a popular streaming library for Scala, could easily be used to transform a CSV file of several gigabytes using limited memory.

Despite being very powerful, fs2 itself can only model data flowing within a single JVM, and not across services; but Kafka lets us apply what we know and love about streaming to build pipelines that spans multiple applications, and still retain the same essential properties:

- Kafka can ensure that consumers receive events in the order they were produced, or, if we don’t care about ordering, lets multiple consumers process events concurrently to achieve higher throughput. If some services care about the order of events and some don’t, it lets us get that best of both worlds by organising consumers into groups.

- ETL pipelines execute in constant memory space, regardless of the amount of data involved. Kafka acts as a buffer between services, keeping track of the latest processed event for every consumer, and making sure consumers are not receiving upstream events as fast as they can process them, but not any faster. Different stages of a pipeline can consume messages at different paces without crashing.

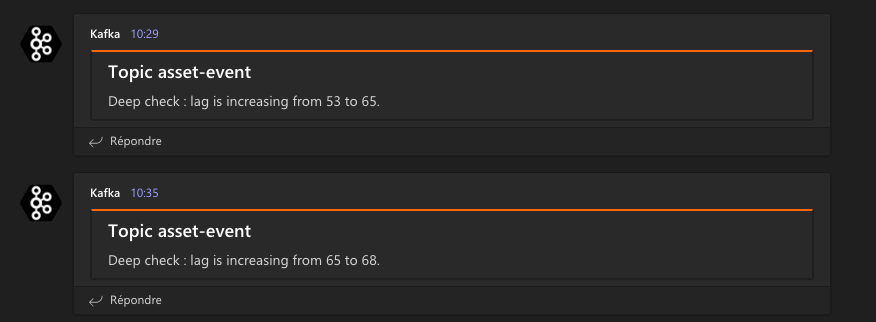

Kafka also gives us the ability to observe what’s going on between our services: we can monitor ETL pipelines, identify bottlenecks and be notified when a service is unusually slow. The main metric we use is the lag, the number of messages that has been produced but not yet acknowledged by a given consumer. We can watch this lag using tools like akhq and Conduktor, and event receive notifications in Microsoft Teams when the lag is abnormally growing.

Scala services

While Kafka can be used with a variety of programming languages using client libraries, we’ve chosen to implement the vast majority of our services using Scala, a statically typed, functional programming language that runs on the Java virtual machine (JVM). When replacing a legacy system, and moving all the data that goes with it, we have to:

- parse the data from various sources, transform it and reject invalid data; make sure this process always work as intended.

- process as much data as we can; make it so users don’t have to wait too long to see their changes happening in the new application.

In short, make it correct and make it fast.

A prime candidate for massively concurrent applications

Regarding the make it fast requirement, Scala is a great candidate for implementing heavy applications thanks to its excellent support for concurrency. The Cats Effect library provides a high-performance runtime that lets us build massively concurrent applications. This runtime provides Fibers, also known as green threads, a threadlike abstraction that is dramatically lighter than JVM threads.

The number of available JVM threads in an application is inherently limited by their heavy nature, but fibers are so lightweight you can reasonably spawn millions of them. Fibers allow us to organise work into semantic units of computation (e.g. one unit per HTTP request in a server), and let the runtime decide how to map these computations to real kernel threads.

Cats Effect makes it remarkably easy to turn a sequential program into a parallel program:

import cats.implicits._

import cats.effect._

// Let's say we have a bunch of user ids, and we want to retrieve users by calling an API endpoint

val userIds: List[Id[User]] = List(Id("a"), Id("b"), Id("c"))

// Here we implement our HTTP call

def getUser(id: Id[User]): IO[User] = ???

// Then we say "call that method for every member of 'userIds'

val users: IO[List[User]] = userIds.traverse(getUser)

In this example, the HTTP calls are sequential. (Don’t worry too much about this IO thing for now).

With a single change on the last line, I can turn them into concurrent HTTP calls, thus greatly improving the speed of

the program.

// Just add 'par' to make the calls in parallel

val users: IO[List[User]] = userIds.parTraverse(getUser)

Cats Effect also provides concurrency primitives such as queues, atomic mutable references, semaphores, resources … Using it as our concurrency toolkit as enabled us to write performant services with ease. That’s it for the make it fast part, for now. How does Scala help us make it correct?

Safety from runtime errors

As a statically typed language, Scala can rule out entire classes of bugs such as null pointer exceptions, and reject incorrect or indeterminate behaviour. As pointed out by Li Haoyi in his article Why Scala?, Scala’s type checker is able to catch the vast majority of the most common bugs in a dynamic language such as Javascript.

Scala’s type system also allows us to model errors as core members of our domain, and distinguish technical failures from errors in our business logic. The latter can be exhaustively checked by the compiler, which will prevent us from forgetting anything. Here’s for example how the compiler would remind me of a missing implementation for a state of the application:

[warn] EitherTExample.scala:25:38: match may not be exhaustive.

[warn] It would fail on the following inputs: Left(ExpiredSubscription(_)), Left(WrongUserName)

[warn] authenticate("", "").value.flatMap({

[warn] ^

[warn] one warning found

I’ve written a fairly long article about asynchronous error handling in Scala if you feel like diving in the details. Here are the key takeaways:

- use sum types to model the possible errors of a program, and treat errors like regular values

- use

Eitherto provide an error channel to your program, rather than using regulartry/catch. This makes errors clearly visible, to you, to your fellow programmers, and to the compiler, which will prevent indeterminate behaviour. - use

EitherTto add an explicit error channel to asynchronous programs (programs that run inIO). This combines the aforementioned benefits of Cats Effect with those of a rigorous error handling strategy. - optionally, use the abstractions provided by Cats MTL to make the code easier to read

More precise domain modelling

Besides the additional safety, having a powerful type system at our disposal lets us precisely model our domain with two goals in mind:

- Making illegal states impossible to represent, which in turn greatly reduces the amount of tests we need to write. (If this feels controversial, check out Julien Truffaut’s talk for an excellent demonstration of how tests and static types complement each other)

- provide our software with an always-up-to-date, living documentation. Types often (I know, not always!) convey more meaning than comments and they always tell the truth. Having more expressive types is a great way to document exactly how your software is supposed to work.

I’ll cover these aspects in more detail when I explain how we parse and validate the incoming data from our legacy application. Until then, here’s a sneak peek:

Algebraic data types

With support for sum types and product types — known together as algebraic data types — Scala lets us express that Essences, the fundamental pieces of data that make up a digital asset, can be:

- A video, that has a resolution, framerate, bitrate, color space etc.

- An audio track, comprised of several audio channels

- A subtitle with a format and a language

// Simplified model

sealed trait Essence

object Essence {

case class Video(resolution: Resolution, framerate: FPS, bitrate: Bitrate) extends Essence

case class Audio(format: AudioFormat, channels: NonEmptyList[AudioChannel]) extends Essence

case class Subtitle(format: SubtitleFormat, locale: Locale)

}

By modelling the data this way, we tell the compiler that Essences can only be one of these three things, and prevent nonsensical combinations such

as a video without a resolution, an audio track without channels, or a subtitle with an audio format. Moreover, when dealing with values of type Essence,

the compiler can enforce exhaustiveness

thus preventing indeterminate behaviour at runtime.

Notice also how the audio channels of an audio essence are modeled using a NonEmptyList. As the name suggests, a NonEmptyList is guaranteed to have at

least one element. Restricted data types like this one are used to reject illegal values as well as to make the complex domain model that is media management a bit

more approachable. While we can always check if a list is empty at runtime, promoting this constraint to the type level reduces human errors and decreases the

number of tests we need to write for our software.

Overall, Scala’s type system, paired with some neat libraries such as Cats, brings us closer programs that are correct by construction.

Coming up next: the details our ETL pipelines

Let’s recap: Canal+, a leader of pay television and film distribution, is rewriting from scratch a major component of the video supply chain. This implies moving massive amounts of data from the old software to the new platform, which, in turn, implies many challenges: how to build a more flexible media asset management platform ?, how to feed content to this new platform?, how to transform data from one platform to the other? …

More generally, the questions that we ask ourselves as a team are

- How to make it flexible? (Given we’ll plenty other needs to address in the future.)

- How to make it resilient? (Especially regarding long-running processes involving shared resources.)

- How to make it correct? (Given the many possible things that can happen in such a complex system.)

- How to make it fast?

None of these questions are entirely easy to answer, but they’re made easier by our choices of architecture: we’re building Mediahub as a distributed system, implemented in Scala and backed by Kafka. This gives us the confidence we need to build a platform that will be the cornerstone of our video supply chain for the next decade.

Now that I have motivated our transition from Edgar to a new platform and introduced the main technical choices that make this transition possible, I can explain how our ETL pipelines work in more detail.

This will be the subject of the next article; until then, take care!

📚 External links

- Digital Asset Management on Wikipedia

- Deploying microservices on microservices.io

- fs2 Crash Course on Youtube

- Combining strict order with massive parallelism using Kafka on Medium

- Akhq on Github

- Condukor’s official website

- Cats Effect’s documentation

- From First Principles: Why Scala? on Li Haoyi’s website

- Cats MTL’s documentation

- Types vs tests on Youtube

- Algebraic data types on Scala Best Practices

- Tagged unions on Wikipedia

- Best Practices of Safe Pattern Matching in a Scala Application on Sysgears